The Himalayas nurture within themselves many clusters of life, human, animal and plant. Nestled between rivers, perched on precarious slopes and flourishing in verdant valleys, they are intrinsic to the Himalayan culture. From the worship of nature and animistic beliefs, the cuisine and crops, to the architecture – all form part of the “Pahari” culture. Exuding warmth, the culture resonates with the spirit of the Himalaya.

The mountains have been witness to mass human migrations traced to almost 3000 years ago, from the Hindukush in the west and the Indo-Gangetic plains in the south. The earliest settlers were from the west and trace their origins to ancient races such as Aryan, Proto-Australoid, Mongoloid, Nordic and Dravidian. The many rivers that originate here, created pockets of habitable terrain, isolated by gorges and cliffs, making them difficult to access. This has, over generations given rise to distinct communities, which share the commonality of the region, but have evolved with responses that are specific to their locale. From the craft, costume, dance and architecture, these variations form an intricate tapestry, rich and fantastic in its details, but essentially woven of the same thread. Across the range from Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh in the west to Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh in the east, these variations fascinate, in the complexity of the stories and the simplicity of their beliefs.

One such community is the Jaunsari tribe, settled between the Tons River in the west and the Yamuna in the east, oral history traces their ancestry to the Pandavas of the Mahabharata, and the Rajputs who would have migrated at the time of the Muslim invasions and integrated with the earlier settlers. They share close links with the Jaunsari communities in Himachal Pradesh. This is especially evident in their architecture.

The village

The village

Building in the hills is a true test of ones understanding of the terrain, the material and the climate. Groups of homes in villages huddle close together perched midway up the slopes, sharing courtyards and routines. The farms take up the most fertile lands near the river and on the edge of the village. The higher reaches of the mountains and the meadows used for grazing the cattle. Most of these activities are subsistence related, with the exception of orchards which were introduced for commercial use, about two generations ago. Most orchards are located on slope lands which are not suitable for other crops. Some nomadic patterns are observed with certain villages being occupied only in winter or at the time of farming, the rest of the time the community being based deeper in the forest.

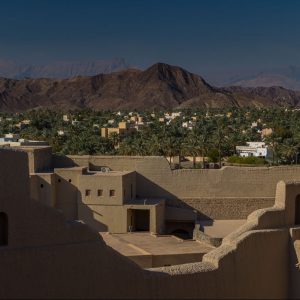

The road has given rise to a new kind of building- the tea-shop, the dhaba and the bank, which all abut the road and feel like the more “public” face of the village. The narrow undulating streets that lead into the village, seeming like one is entering a private home, with a multitude of activities symbiotically taking place, privacy and security taking on different hues. The deeper one goes, the spaces feel like they have been there forever, the courtyard drying vegetables, the women working in the cabbage patch, or the children playing. At the Bisu festival, the large courtyard is a dance space, filled with drums beating and high pitched voices singing in unison. The temple to Mahashu devta, the deity of the Jaunsaris, is prominently located, and is the notional centre of the village- a constant amidst the unpredictable environment. Located on one slope, it’s almost as if the village has two faces, one that is experienced from within and the other which is viewed from across the gorge, from the other slope. From across, it is a picture of slate roofs, wooden pillars, cantilevered balconies. The temple standing out in its roof form and location. The Apple orchards below and above frame the little hamlet. From within, it is an intimate engagement, stone steps, geru coloured walls, bee-boxes, electric wires ending in a broken street light, a vegetable patch and the people. The seemingly “organic” village arrangement, is actually a well-planned layout, perhaps not as we know of planning, but rich in its texture, practical in its use and rooted in its gradual growth.

The home

The home

The homes range from simple single storey linear arrangements to multi storeyed. Cutting the slope to level the land is minimised thus reducing the impact on erosion, creating the linearity which also works for the timber structure for the roof. The homes are oriented to maximise the sunlight, away from trees that may shade and bring in the chill. Typically the lower floor is for the livestock and cattle. In some homes one also sees this used as a store. This insulates the higher levels in the winter. The upper floors are used as living spaces. They are generally of relatively low height and have small openings. The spaces have multiple uses, the kitchen and hearth forming a warm and vibrant centre. The courtyard forms a spill over space for the activities of the house, when the weather permits. Cooking, washing, drying occupy every available flat space, from the roof of the next home, to nooks and crannies that may arise out of the natural terrain. The Balconies and cantilevered floors at the higher levels are ingenious ways to expand usable space, which is difficult to do on the sloped terrain. This is a strong visual characteristic of the region. The form while going vertical, also becomes lighter with the use of timber, and the walls having larger openings, the gabled slate roof blending into the landscape.

The construction and craft

The construction and craft

Stone, mud and timber are the materials that are available across the region, and the buildings are a composition of these. The history of earthquakes in the region have resulted in an innovative style of building called “Kath- koni” which is prevalent throughout the Himalayas.

Cedrus deodara which is a species of cedar native to the western Himalayas is the main timber species that is used. In Kath-koni construction, timber lacing is used in the masonry along the walls and around the corners as a stabilising and strengthening course which helps the structure to be earthquake- resistant. Kath-koni is a type of “cator and cribbage” building construction. The origin of the term is explained as combination of two local terms: kath and koni. The word kath from the Sanskrit word kashtth, which means wood/timber, and koni from the Sanskrit word kona, that is, an angle or a corner. It implies having timber on its corner or angles. It is also known as kath-kona, kath-ki-kanni, koti banal etc.

The timber lacing which alternates with the stone, allows the thickness of the wall to be less than what it would have been as a masonry wall. There are many variations to this from the base of the structure as only masonry, the alternate layers of timber and stone, to only timber framed and panelled walls. Mud is used as a mortar, as well as a rough plaster in some areas. The roof form has varies with the function of the building- the temples having pyramidal and more ornate and complex roof forms which contrast with the simple pitch of the homes. A double or ventilated roof allows for the attic space to be used for drying and for storage. A timber frame with locally available slate is typical to the area, with stones being placed on the roof to weigh it down.

Stories and myths are translated onto the building through wooden carvings, at corners and entries. Wood carving is a craft that is integrated into the building process. The softness of the deodar lends itself to two dimensional and some sculptural forms. The bas-relief work is done prior to constructing the walls and making the tools for this carving is also a craft by itself. The motifs used are inspired by nature and fairly simple and repetitive. The corners are carved with protective symbols and deities, as are the entrances. The fragrance of the deodar wood is a sensual treat and is an integral part of the experience of the space.

Handed down over generations the knowledge of this kind of building is slowly dying out, with fewer practitioners who have the skill and the interest. In many cases the houses have stood for generations without major change and the present generation is not equipped to innovate and modify the structure. With government controls on the cutting of trees, the availability of timber is less, as also of slate. The skill and interest to repair the slate roof is waning and substitutes are being explored. Metal sheets and concrete blocks are finding their way into the streets and corners. The pace in the mountains is slow, controlled by the seasons and the weather, and the process of building is slow. Until recently most of the resources to build were available in the village and the community contributed to build each home. The change in economy and material has eliminated that process. There is a need to rebuild skills, and gain knowledge to innovate, modernise and yet retain the continuity of the stories of the Jaunsaris and the Himalayas, for in their culture and history lie clues to forge the future.