“Will my verandah have two wooden pillars?” asks Mr A as he inspects the verandah of his house, which uses a steel beam to be spanned and actually has no particular use for the said pillars, except that they are his image of what a verandah should be.

“Will this courtyard be protected from the rain?” asks another client, as they explore the plans of their home. We, the architects, patiently explain the idea of a courtyard as a source of light and cross ventilation, apart from the spatial role.

Mangalore tiled roofs, courtyards, wooden crafted balconies, “thinnais”, “padipuras” all form part of the collective memory of the urban upper class, nostalgic about their ancestral homes, looking to assimilate some of the values they represent, in their lives, even if symbolically. Very often it is only the symbols that are fondly remembered and not the thought process behind them. A knowledge that was intrinsic to our forefathers a few generations ago, who had an awareness of what was needed, a knowledge of how to work that with the sun, rain, wind, and the skill to build with materials available around them. A form that is dynamic, alive and responsive to the present. This is the vernacular architecture, we speak of today, where sustainability was a given.

With the change in livelihoods and lifestyle from agrarian to more urban, from joint families in communities to more individualistic nuclear families-the older and traditional architecture has not kept pace with the social and economic changes, and the knowledge held has been almost forgotten, and given way to a new vernacular, which is not necessarily sustainable. This knowledge has been lost not only to the community, but also to architects. How can we change this tokenism at one level and total discontinuity at another? Can an understanding of traditional vernacular architecture give direction to the ideological chaos we are in today? What would this understanding mean to the urban architect and to the rural builder?

The Urban Context

Moving ahead from the traditional, there is definitely a need for a new language of building in our cities today. Be it in the building of a home for a couple that come from different parts of the country and from two different cultures, or in the building of schools that challenge the traditional educational mind-set. While modern architecture is rightly trying to move away from the shackles of casteism and superstition, which were prevalent in traditional building processes also and reflected in the arrangement of villages and planning of homes, one needs to search for the sustainable values in these earlier forms, which are not only timeless, but also may provide some continuity, albeit not literally.

Climate

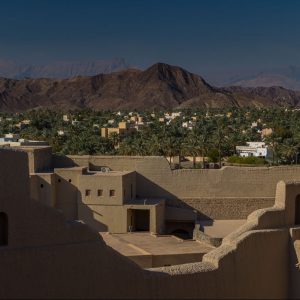

The vernacular aesthetic has evolved from responses to the need for shelter and protection from the elements. These coupled with expressions of craft and organic innovations combine to create inspiring and comfortable spaces that are human in scale and vibrant in spirit.

For example buildings in the Himalayas orient their homes to the Southern direction, to draw in maximum sunlight, especially in winter. The selection of the site of homes and entire villages is based on the understanding of the sun and the power of rain. Natural drainage channels are avoided, as is excessive wind. Similarly, homes along the west coast of India have wide and low overhanging sloping roofs to protect themselves from the monsoon rain, there is more emphasis on cross ventilation, and lower diffused light is preferred, due to the hot and humid climate.

In Bangalore, which is in the temperate zone, the heat is a factor to be contended with, and now the increasing rain. But for most part of the year, the climate is conducive to semi outdoor living, and the challenges of insulation within homes is manageable. The west is a double edged sword, it brings in the breeze as well as the heat. Cavity walls in apartment buildings, to insulate the rooms within, planting intensely along western walls to protect the structure from the heat, verandahs and courtyards in planning to protect and allow for air circulation and double roofs for insulation are some of the concepts used.

Scale

What makes us appreciate the vernacular spaces, how do they convey a sense of romance? An anthropometric study of the scale and proportions of the built and the unbuilt, the textural compositions and craft, gives an insight as to these organic forms are instinctively human in scale.

The courtyard is a ubiquitous characteristic of vernacular architecture all over the world. From being used for cooking, sleeping, eating to providing light and air circulation,it plays multiple roles. In the modern home, in a temperate climate like Bangalore, it can become a private open space, an outdoor workspace, a safe play space for the children of the nuclear family, still playing the role of light and ventilation of the traditional. Another interpretation of the “covered” courtyard, would be a sky-lit space, with air vents to allow air movement, and more specifically hot air to escape. The size of the skylight is critical in not letting it becoming a heat trap.

Similarly the urban verandah is a progression from the traditional, in terms of its size, proportion and material. A long and narrow one, along the length of the home, protects the internal space from the heat and is a living space, a transition between the indoor and outdoor spaces. A squarish one becomes an outdoor dining and workspace, with a plug point for the laptop. The traditional verandah was an interface between the community and the individual in some cases, intimate in its scale, protecting livestock in some cases. In all cases, it is a transition space, one that can be lived in and used in multiple ways, and it protects the inner spaces, climatically and privacy wise.

Material and Craft

Built with materials that are thermally comfortable through the seasons – using methods that are inspiring not only for their common sense but for their craft – vernacular architecture is a living laboratory of trial and error methods over generations. Belonging to an age where the inhabitants had the time to engage with their abodes and the skill and resources to maintain them, many of these are dying for want of the above. There is a need to combine them with modern materials and techniques to retain the original qualities and make them more practical, let them adapt and evolve.

Mud stabilised with cement can be used in the various forms of masonry, from mud blocks and rammed earth to adobe and cob. The addition of cement not only strengthens the walls, allows them to be built with less thickness and creates more space within the building, not compromising on the thermal qualities of mud. Similarly, stone walls which are traditionally thick and require a higher level of craft for building, can be modified to creating a composite wall with a brick, which makes it thinner. Simplifying the bond makes it easier for masons to learn to build and even innovate.

Using timber and the carpentry craft in elements of modern housing enriches the textural quality of the spaces, helps the user to connect to it through its nostalgic value. Balancing the aesthetic with contemporary elements educates the crafts person and gives a direction to the craft. Also, traditionally wood was used in abundance- large sections which would be carved or used structurally were commonplace. As it is no longer available, combining it with mild steel or using trussing systems, is a direction for it to advance.

The Rural Context

In the home of the vernacular- the villages and small towns, the failing economy and the struggle for survival is a common condition across the country. The leisure and resources to build are no longer priorities and in fact the vernacular in some cases represents poverty. They aspire to build “modern” homes, in the new “locally available materials” which are steel and concrete. This contemporary vernacular is not only unsustainable and unsuitable but disturbs the continuity of a culture – making it rootless and lost.

A lack of understanding of the ills of over using industrialised materials, akin to using GM seeds in agriculture, and a loss of respect for the knowledge processes of building has been lost in translation. Climate is understood as superstition and thermal comfort taken for granted. The challenge is to provide solutions that will bridge this gap- that use technology intelligently and in appropriate ways. Keep the vernacular form alive as it is meant to be.

In the Himalayas, using galvanised aluminium sheets to replace the unavailable and difficult to maintain shingles, is a step ahead, retaining the double roof and its form- not replacing it with concrete flat roofs that do not handle the extremes of climate. On the west coast, keeping the traditional form alive- the sloping roof and verandah, and not building boxes that will not sustain in the sea air and the violent monsoon.

While it is romantic to appreciate the old for nostalgia’s sake, it is more relevant to see it for what it is – discard the irrelevant and celebrate the timeless.

A few lessons to learn and questions to ask…

While most vernacular architecture seems instinctive, the instincts have developed over years of working in the same context, observing and learning from what has been built and making minor and refined changes at the next step. Are we setting these kind of precedents in our work today?

As an architecture that is alive and vibrant, where the knowledge of building is not restricted to a set of “specialists” like us, but is shared by the community, roles being played by different members. Can we work with our communities to make them aware of what their needs may be, and empower them with the knowledge to make appropriate sustainable choices and perhaps engage more actively in the building process?

Your effort to demystify and deconstruct the aura around ‘specialists’ echoes the spirit of true democracy and is a fight against a different ,subtle centre of power. The ideas evolve from passionate involvement in all aspects life,with all its myriad colours,the hallmark of your work.The protest ,the seeking and the benevolence of spirit in your body of work will inspire many a young mind.Your blogs stem from your experience,struggle ,insight and search and stand out for its absolute honesty.Best wishes

A few are gifted with the talent to use words & expressions to convey the real story truthfully ! Let your blogs inspire great many more, Best wishes nutty!

Inspired ♥️

Very nice